This is the fourth article in Housing Japan’s ‘Japan’s Best Architects Series’

In a city known for constant reinvention, Kenzo Tange (丹下 健三) stands as perhaps the most influential architect in shaping modern Tokyo. His buildings bridged traditional Japanese aesthetics and bold modernist vision, transforming not just individual sites but entire neighborhoods. For anyone looking at Tokyo real estate today, understanding Tange’s influence reveals how the city’s unique character developed.

His work defined post-war Japanese architecture while establishing principles that continue affecting urban development. Areas touched by his vision, from Hiroshima to Shinjuku, reflect his thinking about how cities should function.

Who Was Kenzo Tange?

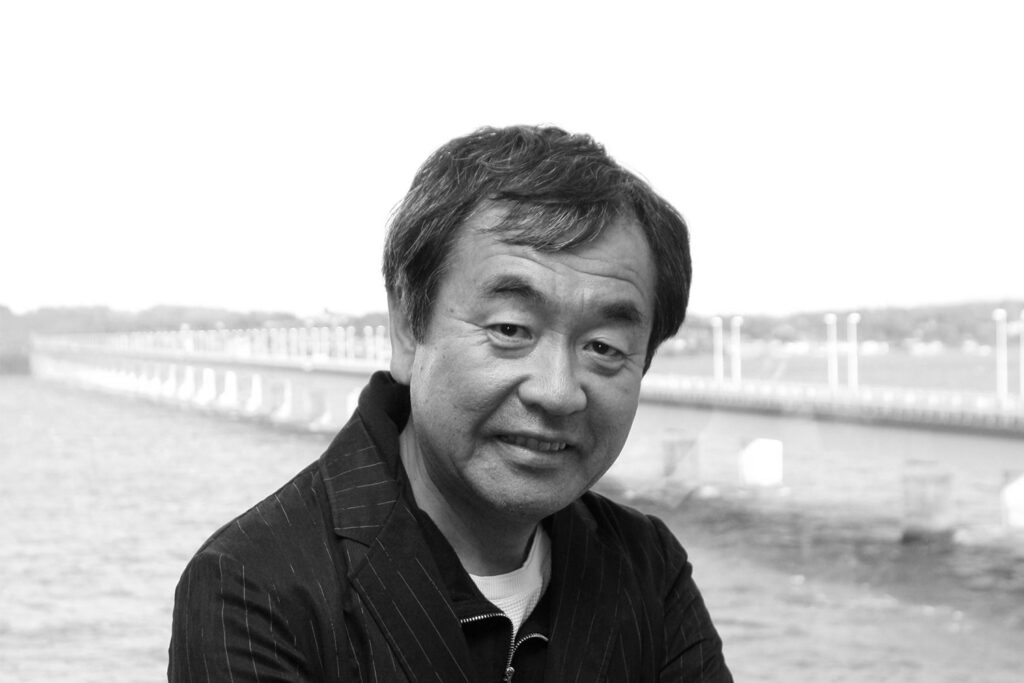

”Kenzo Tange”, 1981. Photo by Hans van Dijk for Anefo / Nationaal Archief, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 NL. Edited by Housing Japan.

Born in Osaka in 1913, Kenzo Tange grew up in Imabari on Shikoku island. His imagination was captured by images of Le Corbusier’s designs in imported magazines, inspiring him to pursue architecture. This early exposure to European modernism shaped his career, though he spent decades blending those ideas with Japanese traditions rather than copying Western styles.

Tange graduated from Tokyo Imperial University in 1938. After working for Kunio Maekawa, who had studied under Le Corbusier, he absorbed modernist principles while developing his own vision. In 1946, he became an assistant professor at Tokyo University, establishing the Tange Laboratory. This design research studio trained some of Japan’s most important architects, including Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki, and Kisho Kurokawa.

What made Tange special was his ability to think at multiple scales simultaneously. He could design a building with exquisite detail while conceptualizing how entire cities should evolve. This dual focus positioned him as an architect of urban futures, someone who imagined how Tokyo might develop over decades.

The Philosophy: Tradition Meets Modernism

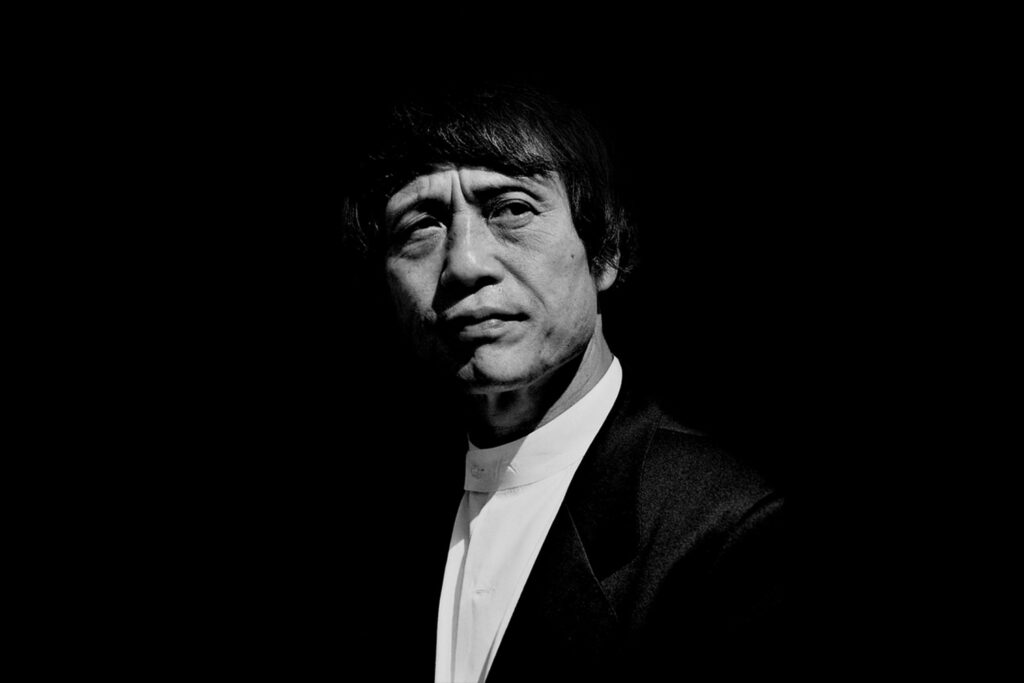

Photo by Morio, “St. Mary’s Cathedral, Tokyo” (2003). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Source: 20030702_2_July_2003_Tokyo_Cathedorale_3_Tange_Kenzou_Sekiguchi_Tokyo_Japan.jpg (2288×1712)

Tange faced a defining challenge for post-war Japanese architecture. How could Japan modernize without losing its cultural identity? His answer was sophisticated, refusing simple fusion while finding deeper connections between seemingly opposite approaches.

He once said, “Tradition can, to be sure, participate in a creation, but it can no longer be creative itself.” This wasn’t rejecting tradition but recognizing that copying old forms wouldn’t serve modern needs. Instead, Tange identified underlying principles in traditional Japanese architecture, the relationship between buildings and nature, modular systems, and creating space through structure rather than decoration.

His buildings featured elements that felt familiar while looking completely modern. He elevated structures on pilotis, creating the same ground relationship as traditional raised floors. He used modular grids echoing tatami mat proportions without traditional materials. His concrete structures had a crafted quality recalling Japanese carpentry.

This approach provided continuity with the past while embracing the future. Properties in areas where Tange worked feel rooted in place despite modern construction.

Revolutionary Urban Planning

While buildings made Tange famous, his urban planning work changed how people thought about cities. In 1960, he presented “A Plan for Tokyo,” addressing the city’s explosive growth. Rather than extending existing patterns outward, he proposed something dramatically different.

His plan called for a massive linear structure extending across Tokyo Bay, an urban spine organizing growth in new ways. The proposal organized the city around transportation rather than traditional districts, creating civic axes allowing Tokyo to grow organically while maintaining functionality.

The plan was never built as proposed, but its influence spread worldwide. It introduced ideas about megastructures, cities as living systems needing adaptation, and relationships between transportation infrastructure and urban form. These concepts contributed to the Metabolist movement defining Japanese architecture in the 1960s.

For Tokyo property buyers today, understanding Tange’s philosophy provides insight into the city’s development. Areas like Shinjuku became major centers reflecting his thinking about creating multiple focal points. The emphasis on transit-oriented development echoes ideas he championed.

Major Kenzō Tange Works in Tokyo

Tange’s buildings in Tokyo demonstrate his range, from intimate spiritual spaces to massive civic monuments.

Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, Shinjuku – Completed 1990

Completed in 1991, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku represents Tange’s later approach to monumental civic architecture. The complex consists of two towers rising 243 meters, making them among Tokyo’s tallest structures at the time of completion.

The building’s design references Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris and traditional Japanese temple architecture, with vertical elements creating a soaring presence on Shinjuku’s skyline. The towers split at the 33rd floor, creating distinctive silhouettes visible across Tokyo.

Free observation decks on the 45th floors offer panoramic views of the city and, on clear days, Mount Fuji. The building houses Tokyo’s government offices and has become a landmark defining Shinjuku’s character as a major urban center.

The project demonstrates Tange’s continued relevance in his later career, creating buildings that balance functional requirements with symbolic importance. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building anchors the Shinjuku subcenter, contributing to the area’s development as a business and administrative hub.

Shizuoka Press & Broadcasting Centre, Ginza – Completed 1967

Completed in 1967, the Shizuoka Press & Broadcasting Centre in Ginza shows Tange’s interest in Metabolist ideas about flexible, growing architecture. The building consists of a central concrete core with prefabricated office units cantilevered outward like tree branches.

The design reflects Metabolist thinking about cities as living organisms needing adaptation. Rather than designing fixed buildings, Metabolists proposed structures with permanent cores and replaceable components. While rarely fully realized, this influenced how architects thought about flexibility in urban buildings.

The building remains a Ginza landmark, its distinctive branching form instantly recognizable.

Yoyogi National Gymnasium, Shibuya – Completed 1964

When Tokyo hosted the 1964 Olympics, the games symbolized Japan’s post-war recovery. Tange’s sports facilities, particularly the Yoyogi National Gymnasium, became architectural symbols of that recovery.

The gymnasium’s most striking feature is its suspended roof, hung from massive steel cables anchored to concrete masts. This structural system allowed vast column-free interior spaces, representing cutting-edge engineering. The curved rooflines referenced traditional Japanese architecture, creating visual connections to temple roofs without copying them.

The complex includes two buildings, a larger gymnasium seating about 15,000 people and a smaller annex for about 5,000. The buildings sit in Yoyogi Park, and their curved forms complement the natural setting.

The project demonstrated Japanese architects could execute technically demanding projects at international standards. The gymnasium and surrounding Yoyogi area attract interest from property buyers today.

Notable Work by Kenzō Tange Throughout The Rest of Japan

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Museum, Hiroshima – Completed 1954

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, completed in 1955, perhaps encapsulates Tange’s philosophy well. The city commissioned him to create a memorial for atomic bomb victims while designing a museum documenting what happened.

Tange designed the museum as a concrete structure elevated on massive pilotis, lifted as if floating. The building’s simplicity creates powerful presence without overwhelming the landscape. A large plaza extends toward the preserved Atomic Bomb Dome, creating a clear axis organizing the entire park.

Beyond the museum, Tange designed the park’s central cenotaph, which became one of the most recognized peace symbols worldwide. The structure consists of a curved concrete arch, its shape inspired by ancient Japanese burial mounds from the Kofun period. The arch frames a view toward the Atomic Bomb Dome, creating visual connection between monument and preserved building while suggesting both protection and opening.

The project established Tange’s international reputation, demonstrating how modern architecture could address profound emotional and historical subjects. The concrete surfaces weather naturally, aging appropriately for a memorial.

Kenzō Tange’s International Works

While Tange’s reputation was built on Japanese projects, his international work demonstrated his ideas could translate to different contexts.

The Kuala Lumpur International Airport in Malaysia, completed in 1998, shows Tange applying his ideas to tropical conditions. The building features dramatic roof structure providing shelter while allowing natural ventilation. The forest-like columns inside create spaces feeling both monumental and human-scaled.

In Singapore, his work on buildings like UOB Plaza demonstrated how his high-rise design approach could work in different urban contexts. For Tokyo property buyers, these international projects demonstrate the global recognition Tange achieved, adding context to his Tokyo buildings.

The Fiera District in Bologna, Italy, and various projects in the Middle East and Asia showed his ideas about urban form could work in completely different settings. This international success reinforced Tokyo’s position as a design capital.

The Metabolist Movement

In 1960, young architects including Kisho Kurokawa and Fumihiko Maki published a manifesto proposing a new approach. They argued buildings and cities should be designed like living organisms, with cores that last and components that can be replaced.

Tange wasn’t officially a Metabolist but mentored the movement’s key figures. His urban planning ideas strongly influenced their thinking. His 1960 Tokyo Bay plan articulated ideas the Metabolists would develop further.

The movement produced few fully realized buildings, Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower being the most famous, but its influence was substantial. The emphasis on adaptability affected how architects approached urban projects. For Tokyo real estate, these ideas contributed to the city’s ability to rebuild and adapt.

Kenzō Tange’s Impact on Tokyo Real Estate Today

Tange’s influence on Tokyo operates at multiple levels. Neighborhoods with his buildings attract interest from buyers. Areas around Yoyogi Park benefit from proximity to his Olympic facilities. Properties with views of his buildings draw attention from prospective buyers.

His urban planning concepts influenced how Tokyo developed. The emphasis on transit-oriented development, creating multiple urban centers, and designing for adaptability all reflect ideas Tange championed. These planning principles helped Tokyo become one of the world’s most functional large cities.

For property buyers, understanding Tange’s philosophy provides insight into neighborhood character. Areas embodying his ideas about connection to nature, human-scaled public spaces, and relationship to transit infrastructure have distinct qualities.

International buyers appreciate areas influenced by Tange because they offer something distinctive. These neighborhoods feel thoroughly modern while maintaining strong connections to Japanese architectural traditions.

Kenzō Tange’s Later Career and Legacy

As Tange’s career progressed, his work became more monumental. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku, completed in 1991, exemplifies this approach. The massive twin-tower complex makes a bold statement about civic architecture.

Throughout his career, Tange maintained his teaching practice, training generation after generation of architects. His students include multiple Pritzker Prize winners and principals of major architecture firms worldwide.

Tange continued working until his death in 2005 at age 91. His firm, reorganized as Tange Associates, continues operating today.

Conclusion: Building the Future

Kenzo Tange transformed Japanese architecture by showing how traditional ideas could inform modern buildings without limiting them. His work proved that concrete and steel could create spaces with spiritual resonance, that massive structures could maintain human scale, and that modern cities could grow organically.

For Tokyo, his influence extends far beyond the buildings he designed. His urban planning concepts shaped how the city developed, affecting everything from transit networks to building codes. His emphasis on quality construction raised standards across the industry.

Today, as Tokyo continues evolving, the principles Tange championed remain relevant. His emphasis on flexibility, on designing for change while maintaining quality, speaks to current concerns about sustainable development.

Whether you’re considering property purchase in Tokyo or simply interested in architecture, understanding Tange’s legacy provides valuable perspective on how great cities develop. His buildings and ideas shaped one of the world’s most dynamic urban environments.

Q&A: Common Questions About Kenzo Tange and Tokyo Real Estate

What makes Kenzo Tange buildings special for property buyers? Tange’s buildings typically reflect quality construction and thoughtful spatial design. His attention to detail and structural integrity creates lasting architectural significance.

How did Kenzō Tange influence Tokyo’s development? His urban planning concepts, particularly about transit-oriented development and creating multiple urban centers, influenced post-war Tokyo’s development. His emphasis on connection to nature affected planning standards throughout the metropolitan area.

Where can I experience Kenzō Tange architecture in Tokyo? Yoyogi National Gymnasium remains his most accessible major work, with the park surrounding it free to visit. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku offers observation decks open to the public.

Why is Metabolism important for understanding Tokyo real estate? The Metabolist movement, which Tange influenced, promoted ideas about flexible, adaptable architecture that affected how Tokyo developed. The emphasis on designing for change contributed to Tokyo’s ability to rebuild.

Did Kenzō Tange design residential properties? While Tange is known for public buildings, he designed some residential projects early in his career and influenced residential design through his students and the broader architectural culture.